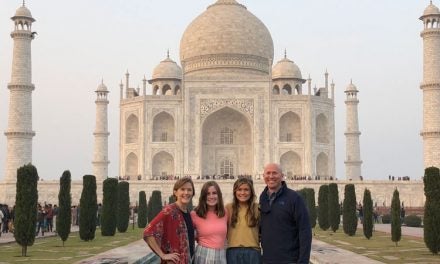

Nolan Turner is following in his dad’s footsteps on the football field—for the Tigers instead of the Tide.

Nolan Turner remembers his father Kevin coaching him on a neighborhood youth football team as vividly as he foresaw following in his footsteps onto collegiate fields. “I always envisioned myself playing college football,” Nolan recalls. “I didn’t know where it was going to be or how it was going to happen. But that was always one of my dreams.”

Dreams have a funny way of coming true, but not always in the way you’d think. By his senior year at Vestavia Hills High School, Nolan was on no one’s radar as a major college football prospect. His only invitation was to be a walk-on at a school or two, including the one in Tuscaloosa where Kevin launched a career that took him to the National Football League.

Someday Nolan may land in the NFL. But if he does, it will be after having veered east rather than venturing west, heading to Clemson instead of Alabama. Today he has two national championship rings from his redshirt sophomore season with the Tigers. Each came courtesy of a title game victory over the Crimson Tide.

Photo by Carl Ackerman/Clemson Athletics

The first came at the conclusion of Nolan’s redshirt season, a 35-31 comeback win over Alabama. He was fully engaged in the second title with two solo tackles and two assists when Clemson drubbed the Tide 44-16.

Going into the 2019 campaign, Nolan is credited with 58 tackles (3.5 for loss), four passes broken up, a sack and an interception where he returned 24 yards in 435 snaps over 28 career games. “To look back now from where we are and the success we’ve had at Clemson and for me to be a part of it,” Nolan says. “Yeah, it’s really special, and to have made it this far is pretty cool. I’m glad I’m still getting to do it.”

But there was a time when he didn’t fully grasp the significance of a game like that, or the star status his father had on the gridiron. A product of Prattville High School, Kevin was a member of the 1984 Alabama high school state championship team. He went on to the University of Alabama, where he was a strong blocking fullback for Siran Stacy and Bobby Humphrey.

Bobby Humphrey remembers Kevin as a dedicated blue-collar worker while tailbacks like himself got the glory. “But not only was he one of the better blockers to put on the uniform at Alabama, he was also just one hard worker,” Bobby recalls. “He just put on his hardhat and went to work every day—in the weight room, on the field during workouts. He was just one of those guys who was very dependable.”

Kevin’s star shined more brightly in the NFL too. He was a third-round selection of the New England Patriots in the 1992 NFL draft and played three seasons for them and then another five with the Philadelphia Eagles. Through those years and beyond, his son Nolan was paying attention too, to his work ethic, perseverance, and how he treated people. “He kind of loved everybody, and (everybody) loved him because of that,” Nolan says. “He had a long, successful career in the pros, which is not easy to do, and that’s all because of his work ethic. I’d say I idolized those traits about him.”

But Kevin’s storybook tale took an unfortunate turn when it came to his health. He was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in June 2010 and passed away on March 24, 2016, from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Nolan’s mom JoyceMarie Turner recalls Kevin’s condition being indescribably horrific. “You know your kids are watching it…and they were so devastated. There wasn’t anything I could do to fix the pain they had watching their dad suffer,” she recalls. “That was the worst part for me, other than knowing what Kevin was going through. And every day it got worse.”

Buddy Anderson, the Vestavia Hills High football coach, recalls how it affected Nolan too. “I think his dad was diagnosed when (Nolan) was in the seventh grade,” Anderson says. “(Throughout) his whole time growing up that was a tough time because his dad’s health declined rapidly with that ALS. I think football was an outlet for him. It gave him a chance to get out some of his frustration.”

Despite what was going on at home, Anderson says Nolan was one of the best players who came through his Rebels program, but the safety/wide receiver wasn’t getting serious attention from major college football programs as he wrapped up his high school career. “I put him on all the lists you’re supposed to put them on,” the coach recounts. “When (college) coaches would come by, I’d give them his name. Of course, he had gone to camps, and I definitely felt he could play.”

With no scholarship offers, Nolan planned to go to Alabama as an invited walk-on—until he got a call from a familiar source. Clemson coach Dabo Swinney played at Alabama with Kevin, and as adults the two worked together. “In ’08 when I was the interim coach, I actually hired Kevin to come up, and he was a GA (graduate assistant) for me for the last part of my interim time. We ended up going to the Gator Bowl that year, and all of our families went.”

Dabo still has a picture of a 9-year-old Nolan at the Gator Bowl with his own sons and other kids on the practice field. He knew Nolan well, but that didn’t mean he could offer him a scholarship. “We really weren’t recruiting DBs that year,” he says. “In recruiting, everything’s about timing. We didn’t have any spots, and all of a sudden after the national championship game that year out in Arizona, I had four juniors who decided to go pro early.”

It was then that Dabo took a look at Nolan’s senior tape. “I compared him to the other guys, and it was like, ‘Man, this guy can play,’” the Clemson coach recalls. “Then I called Buddy Anderson. I knew what I saw on tape, and I didn’t want to have a biased opinion. Buddy, who’s been coaching for 50 years there, said he’s as good as he’s ever had. He really was disappointed with the whole recruiting process and couldn’t understand why Nolan didn’t have D1 offers.”

It was then that Dabo took a look at Nolan’s senior tape. “I compared him to the other guys, and it was like, ‘Man, this guy can play,’” the Clemson coach recalls. “Then I called Buddy Anderson. I knew what I saw on tape, and I didn’t want to have a biased opinion. Buddy, who’s been coaching for 50 years there, said he’s as good as he’s ever had. He really was disappointed with the whole recruiting process and couldn’t understand why Nolan didn’t have D1 offers.”

That would change when Dabo came to town though. Nolan knew he was coming, but he didn’t know what was in store. Anderson recalls the exchange in his office. “Nolan, I want you to know something,” the coach remembers Dabo saying. “Your dad and I were good friends, but I’m going to get the best person I can to play at Clemson. This has nothing to do with your dad and my friendship. You’re the best one for us, and I’m offering you a scholarship.”

“Nolan’s sitting there and all of a sudden said, ‘Sir? What did you say?’ (I) said I’m offering you a scholarship. Would you like to come to Clemson? (Nolan) said, ‘I’d love to.’”

Nolan’s decision didn’t waver when Alabama coach Nick Saban visited him a day later, still offering invited walk-on status. “When he left, I said, ‘Nolan, you’ve got some decisions to make.’ He said, ‘Coach, I’m going to Clemson.’ I said, ‘Okay, I support you.’”

Photo by David Platt/Clemson Athletics

Kevin passed away a few weeks after Nolan’s college decision. But, as JoyceMarie saw it, he died a happy man. “It was like he let himself go once he knew that Nolan was going to be in the hands of Dabo,” she says. “Playing for Dabo, having Dabo as his mentor now in his life was like Kevin finally just decided to give up the fight. He was just so thankful that he was getting that opportunity to be with Clemson and Dabo. We could not have been more thankful for that.”

Dabo says it’s amazing how God opens doors and creates opportunities. “I really believe it was kind of meant to be and kind of divine intervention how it all worked out,” he says. “And what a great moment for me to see KT have the peace in knowing that Nolan was coming to Clemson, and it was something he had earned. (Kevin) knew (Nolan) was going to be in good hands with a lot of good people up here who were going to love him.”

And that’s exactly what happened. Nolan was an immediate success on the field and is a crucial team player for the Tigers as he heads into his fourth year this fall. “What a player he’s become,” Dabo continues. “Man, he had a great year (last season). He was a starter for us in our dime (coverage) package. He’s still got two years left. He’s going to have a heck of a career. I’m really proud of him.”

Three years removed from high school, Nolan could do as those other Clemson Tigers did in clearing the road for him. He could choose to make himself eligible for the NFL Draft. But the financial management major says that’s not going to happen. “I’ll be at Clemson for five years,” he told us this summer. “I’ll play two more seasons and see where it takes me after that.”